|

| The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, ca. 1969 |

The Family Dog on The Great Highway, 660 Great Highway, San Francisco, CA

The

Family Dog was a foundation stone in the rise of San Francisco rock,

and it was in operation in various forms from Fall 1965 through the

Summer of 1970. For sound historical reasons, most of the focus on the

Family Dog has been on the original 4-person collective who organized

the first San Francisco Dance Concerts in late 1965, and on their

successor Chet Helms. Helms took over the Family Dog in early 1966, and

after a brief partnership with Bill Graham at the Fillmore, promoted

memorable concerts at the Avalon Ballroom from Spring 1966 through

December 1968. The posters, music and foggy memories of the Avalon are

what made the Family Dog a legendary 60s rock icon.

In the Summer of 1969, however, with San Francisco as one of the fulcrums of the rock music explosion, Chet Helms opened another venue. The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, on the Western edge of San Francisco, was only open for 14 months and was not a success. Yet numerous interesting bands played there, and remarkable events took place, and they are only documented in a scattered form. This series of posts will undertake a systematic review of every musical event at the Family Dog on The Great Highway. In general, each post will represent a week of musical events at the venue, although that may vary slightly depending on the bookings.

If anyone has memories, reflections, insights, corrections or flashbacks about shows at the Family Dog on the Great Highway, please post them in the Comments.

|

| 660 Great Highway in San Francisco in 1967, when it was the ModelCar Raceway, a slot car track |

The Edgewater Ballroom, 660 Great Highway, San Francisco, CA

As early as 1913, there were rides and concessions at Ocean Beach in San Francisco, near the Richmond District. By 1926, they had been consolidated as Playland-At-The-Beach. The Ocean Beach area included attractions such as the Sutro Baths and the Cliff House. The San Francisco Zoo was just south of Playland, having opened in the 1930s. One of the attractions at Playland was a restaurant called Topsy's Roost. The restaurant had closed in 1930, and the room became the Edgewater Ballroom. The Ballroom eventually closed, and Playland went into decline when its owner died in 1958. By the 1960s, the former Edgewater was a slot car raceway. In early 1969, Chet Helms took over the lease of the old Edgewater.

|

| One

of the only photos of the interior of the Family Dog on The Great

Highway (from a Stephen Gaskin "Monday Night Class" ca. October 1969) |

The Family Dog On The Great Highway

The

Great Highway was a four-lane road that ran along the Western edge of

San Francisco, right next to Ocean Beach. Downtown San Francisco faced

the Bay, but beyond Golden Gate Park was the Pacific Ocean. The aptly

named Ocean Beach is dramatic and beautiful, but it is mostly windy and

foggy. Much of the West Coast of San Francisco is not even a beach, but

rocky cliffs. There are no roads in San Francisco West of the Great

Highway, so "660 Great Highway" was ample for directions (for reference,

it is near the intersection of Balboa Street and 48th Avenue). The

tag-line "Edge Of The Western World" was not an exaggeration, at least

in American terms.

The Family Dog on The Great Highway was

smaller than the Bill Graham's old Fillmore Auditorium. It could hold up

to 1500, but the official capacity was probably closer to 1000. Unlike

the comparatively centrally located Fillmore West, the FDGH was far from

downtown, far from the Peninsula suburbs, and not particularly easy to

get to from the freeway. For East Bay or Marin residents, the Great

Highway was a formidable trip. The little ballroom was very appealing,

but if you didn't live way out in the Avenues, you had to drive. As a

result, FDGH didn't get a huge number of casual drop-ins, and that

didn't help its fortunes. Most of the locals referred to the venue as

"Playland."

Chet Helms had opened the Family Dog at 660 Great Highway to much fanfare on June 13, 1969, with a packed house seeing the Jefferson Airplane and The Charlatans. One of the goals was that the Dog would feature mostly San Francisco bands and a variety of smaller community events and groups. Since so many San Francisco bands were successful, and had record contracts, this didn't confine the venue to obscurity. A lot of great bands played the Family Dog in 1969, but the distant location and the gravitational pull of major rock events hosted elsewhere in the Bay Area kept the Family Dog isolated. We know only the most fragmentary bits about music played, events and audiences throughout the year. Despite the half-year of struggle, Helms had kept the Family Dog on The Great Highway afloat. He had entered the new year of 1970 with a new plan.

- For a complete list of Family Dog shows (including FDGH), see here

- For the previous entry (April 24-26, 1970 Quicksilver Messenger Service) see here

- For a summary and the link to the most recent entries in this series, see here

Chet Helms had re-opened the Family Dog on the Great Highway on a new footing at the end of January, 1970. Instead of a mixture of community events, the Dog had focused on weekend rock concerts featuring major San Francisco bands. The Dog headliners were Fillmore West headliners, too, so the venue was would be more of a destination than just a hang-out. But the momentum hadn't lasted. The big headliners faded away after April, an implicit note that Helms could no longer afford to guarantee bands a payday. Starting in May, while the Family Dog remained focused on weekend bookings, the bands weren't Fillmore West material.

Big Brother and The Holding Company had returned to headline the Family Dog for the third weekend since February. They were a huge name, of course, but without Janis Joplin fronting the band, they weren't a huge draw. The original four members (Sam Andrews, James Gurley, Peter Albin and Dave Getz) were all still in the band, along with an additional guitarist (David Schallock). Big Brother was actually a pretty good band, and they were working on an album with producer Nick Gravenites. The underrated Be A Brother would come out around July, to little fanfare.

Aum was a trio featuring guitarist Wayne Ceballos. Ironically, they were booked by Bill Graham's Millard Agency. Graham and Helms were competitors, but this did not extend so far as to cutting Helms out of Millard acts. Aum had released its second album in late 1969. Resurrection had been released on Fillmore Records, Graham's own label (distributed by Columbia). Aum had been booked fairly prominently around the Bay Area in 1969, often opening for the Grateful Dead (booked by Millard at the time as well). The band had faded away a little bit by 1970, and would soon break up (Ceballos continues to perform, now based out of Austin, TX).

The Backyard Mamas are familiar to me from various listings, but I don't really know anything about them.

Folk duo Craig Nuttycombe and Dennis Lambert had been in the Eastside Kids in Southern California. Their album on A&M Records had been recorded at Nuttycombe's home.

May 8-10, 1970 Family Dog on the Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen/Osceola/Southern Comfort (Friday-Sunday)

Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen had only relocated to Berkeley from Ann Arbor, MI in the Summer of 1969. Their unique blend of dope-flavored Western Swing and old-time rock and roll instantly found an audience. One of the Airmen's first gigs had been at the Family Dog in August 1969, and they had opened shows regularly at the venue, for the Grateful Dead and for the Youngbloods. While they were the headliners at this show, the Airmen were still a local club act. They would not be signed to Paramount ABC to record their debut album until 1971.

Osceola had been playing the Family Dog since September of 1969. They would play the Dog many times, and played

around the Bay Area regularly until at least 1972. Osceola

lead guitarist Bill Ande was a transplant from Florida. He had played

and recorded with some modestly successful bands, like the R-Dells, the

American Beetles (really), who had then changed their name to The

Razor's Edge and had even played American Bandstand. Come '69, Ande

had relocated to San Francisco to play some psychedelic blues. The

musicians he linked up with were all Florida transplants as well, so

even though they were a San Francisco band, they chose the name Osceola

as an homage to their roots. To some extent, Osceola replaced Devil's

Kitchen as the informal "house band" at the Family Dog, insofar as they

played there so regularly.

Osceola was a five piece band with two drummers, and played all the local ballrooms and rock nightclubs. Ande was joined by guitarist Alan Yott, bassist Chuck Nicholis and drummers Donny Fields and Richard Bevis. Osceola was a successful live act, but never recorded. Almost all of the band members would return to the Southeast (mainly Tallahassee and Atlanta) in the mid-70 to have successful music careers.

Around May, 1969, drummer Bob Jones and some other local musicians formed a band modeled on Booker T and The MGs. The idea was that they would be a complete studio ensemble, and also record and perform their own music. All of the musicians were regulars in the busy San Francisco studios, often playing for producer Nick Gravenites. The members of Southern Comfort were:

Fred Burton-lead guitar [aka Fred Olson, his given name]

Ron Stallings-tenor sax, vocals

John Wilmeth-trumpet

Steve Funk-keyboards

Art Stavro-bass

Bob Jones-drums, vocals

Ron

Stallings had been in the T&A Blues Band with Kahn and Jones. He

would turn up later with Kahn in Reconstruction in 1979. In late 1969, Southern

Comfort had been signed by Columbia Records, and Gravenites was

signed up as the producer. At this period of time, Gravenites was also

working with Mike Bloomfield, Brewer And Shipley and later Danny Cox

(who shared management with Brewer And Shipley), and the individual members worked on many of those records. Meanwhile, Southern Comfort gigged steadily around the Bay Area.

According to Jones, Nick Gravenites found himself overcommitted in the studio, and turned the production of the Southern Comfort album over to John Kahn. Kahn and Jones were close friends, so this was fine with the band. Gravenites had been using the musically trained Kahn as an arranger and orchestrator anyway, so this was more like a promotion rather than a new assignment. Kahn was listed as co-producer on the Southern Comfort album, and he filled in a few gaps--co-writing songs, helping with arrangements, playing piano--but not playing bass. Columbia released the Southern Comfort album in mid-1970. At the time of this Family Dog show, the album had probably just been released.

|

| A Randy Tuten flyer for Big Mama Thornton, Sandy Bull, Mendelbaum and Doug McKechnie and His Moog Synthesizer at the Family Dog on The Great Highway, May 15-16, 1970 |

May 15-16, 1970 Family Dog on the Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Big Mama Thornton/Sandy Bull/Mendlebaum/Doug McKechenie and His Moog Synthesizer (Friday-Saturday)

Big Mama Thornton (1926-1984) had been a popular and important blues singer since the early 1950s. She had originally recorded “Hound Dog” in 1952, years before Elvis Presley, and her 1968 version of “Ball And Chain” was a huge influence on Janis Joplin’s more famous cover version (as Janis was the first to admit). However, Thornton’s successful records did not lead to her own financial success, and despite being a fine performer she was notoriously difficult to work with. Big Mama had played a number of weekends at the Fillmore in 1966, including opening for both the Jefferson Airplane (October 1966) and the Grateful Dead (December 1966). Unlike many blues artists who played the Fillmore the first year, she had not reappeared. There's no explanation as to why she hadn't been seen at rock venues since. Big Mama had played at the Family Dog back in July '69, but she had almost no rock profile.

From today's perspective, Big Mama Thornton seems like a very interesting performer, and no doubt she was, but in 1970, to the mostly teenage audience, she would have just seemed old (of course, in 1970 she would have been just 43). Her current album would have been The Way It Is, on Mercury.

Sandy Bull was a solo guitarist, a unique and remarkable performer whose elaborate fingerpicking was enhanced by various electronic looping effects. Although appealing to a rock audience, more or less, Bull was the type of performer whose audience remained seated. He had played the Bay Area many times over the years, usually at The Matrix. At this time, his most recent album would have been E Puribus Unum, released on Vanguard the previous year. Bull had played all the instruments himself, and the music was hardly rock.

Mendelbaum had arrived from Wisconsin at the end of Summer 1969. They featured lead guitarist Chris Michie, who went on to play with Van Morrison and others, and drummer Keith Knudsen (who would play with Lee Michaels and then the Doobie Brothers). By May of 1970, Mendelbaum were regulars around the Bay Area rock club scene. In 2002, the German label Shadoks would release a double-cd of Mendelbaum material from 1969 and '70 (both live recordings and studio demos).

|

| Doug McKechnie and his Moog synthesizer, ca 1968 |

Doug McKechnie performed on his Moog Synthesizer. He had previously played the Family Dog under the name SF Radical Lab, back on August 31, and then again on the weekend of September 19-21. At this time, there was a little bit of awareness about synthesizers, through Walter Carlos' 1968 album Switched On Bach record and George Harrison's 1969 Electronic Sounds lp, but they were still pretty mysterious. No one would have seen a Moog Synthesizer live, so in that respect McKechnie's performance would have been quite interesting.

Doug McKechnie's history was unique in so many ways. Around about 1968, McKechnie had lived in a warehouse type building on 759 Harrison (between 3rd and 4th Streets-for reference, 759 Harrison is now across from Whole Foods). Avalon Ballroom soundman and partner Bob Cohen lived in the building, and Blue Cheer (and Dan Hicks and The Hot Licks) practiced upstairs. One day, McKechnie's roommate Bruce Hatch acquired a Moog Synthesizer, and the instrument arrived in boxes, awaiting assembly. At the time, a synthesizer was like a musical unicorn, only slightly more real than a myth. Hatch had the technical ability to assemble the machinery, but he was basically tone-deaf. So McKechnie focused on actually making music on the Moog.

McKechnie and Hatch referred to their enterprise as Radical Sound Labs. Word got around--McKechnie helped the Grateful Dead record the strange outtake "What's Become Of The Baby" on the 1969 Aoxomoxoa sessions in San Mateo (his memories are, uh, fuzzy). Thanks to the Dead, McKechnie and his Moog--the size of a VW Bus--can be seen in the Gimme Shelter movie, providing peculiar music on a gigantic sound system for the anxious masses.

[update 20230515: fellow scholar Jesse Jarnow points out that the founder of Rainbow Jam Lights, Richard Winn Taylor, became an important Hollywood animation pioneer]

This May weekend featured an all jazz-rock bill, and the performances would certainly be of a very high quality. None of the groups were particularly popular, unfortunately, so attendance was probably thin.

Georgie Fame (b. Clive Powell in 1943) had been a huge star in England in the 60s. In the early 60s, Fame played legendary gigs at the Flamingo Club for American servicemen. Fame sang and played organ, and was heavily influenced by Mose Allison, James Brown and others. He merged soul, blues and jazz in a unique English way. Without Georgie Fame, there would be no Van Morrison (Fame was an anchor of Van's live bands in the 80s and 90s, and they would make an album together). Fame had three #1 hits in England, "Yeh Yeh" (1964), "Get Away" ('66) and "The Ballad Of Bonnie and Clyde" (1967). Only the latter was a hit in the States, however. Georgie Fame never toured America with other British Invasion acts, reputedly because he had Nigerians and Jamaicans in his band.

In 1969, Fame reformulated himself with a sophisticated band called Shorty. They released an album on Epic in early 1970. It was supposedly recorded live, but it sounds to me like it was actually recorded live in the studio with crowd noise dubbed in. In any case, there was a mixture of originals and jazzed up covers of blues songs like "Parchman Farm" and "Seventh Son." The band seemed to be a quintet with Fame on Hammond organ, an electric guitarist and a tenor saxophone. Shorty seems to have done a short American tour, as they had just played at the Fillmore West (opening for Lee Michaels and the Faces from May 7-10).

The Jerry Hahn Brotherhood was a newly-formed, only-in-San-Francisco band, and they had gotten a fairly big advance from Columbia. Columbia was heavy in the "jazz-rock" vein, and had hit it big with Blood, Sweat & Tears and Chicago. They would release an album in the middle of the year.

Jerry Hahn was a pretty serious jazz guitarist, based in San Francisco, and he had played with John Handy and Gary Burton, among others. As "jazz-rock" became a thing, Hahn seems to have wanted to play in a more rock vein. Organist Mike Finnegan was newly arrived from Wichita, Kansas. He was not only a great Hammond player, he was a terrific blues singer too (also, he was 6'6'' tall, and had gone to U. of Kansas on a basketball scholarship, making him the Bruce Hornsby of his era). Filling out the band were local jazz musicians Mel Graves on bass and George Marsh on drums. Marsh had just left the Loading Zone, an interesting (if perpetually struggling) Oakland band.

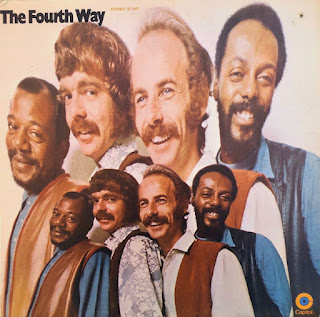

The Fourth Way was an interesting electric jazz-rock band. There were a lot of bands in the Bay Area fusing rock, jazz and electricity, but Fourth Way did it in a less frantic style than Miles Davis or the Tony Williams Lifetime. Fourth Way did release three albums on Capitol, now long out-of-print. Bandleader Mike Nock, formerly pianist with Yusef Lateer, Steve Marcus and many others played electric keyboards. The lead soloist was electric violinist Mike White, best known for playing with the John Handy Quintet. Bassist Ron McClure had played with Handy, and then with a Charles Lloyd Quartet lineup when it was based in San Francisco (along with Keith Jarrett and Jack DeJohnette). Drummer Eddie Marshall rounded out the quartet.

|

| This Susanna Millman photo from the old Grateful Dead Tapers Compendium shows Owsley tapes for Shorty, Fourth Way and Jerry Hahn Brotherhood from May 23, 1970 |

An intriguing detail about this set of concerts is that Owsley preserved tapes of all three bands from the Saturday night show (May 23, 1970). A long-ago Susanna Millman photo of the Grateful Dead Tape Vault, from the old Grateful Dead Tapers Compendium, which at the time included Owsley's material , shows tape boxes for all three bands. After Owsley had been busted with the Grateful Dead in New Orleans, back at the end of January, he was no longer able to travel with them due to a parole violation from a previous arrest. At least on some occasions, Owsley was the soundman at the Family Dog, and as a result some interesting tapes from 1970 were preserved. The current status of these three tapes is unknown, but I remain ever hopeful.

For the next post in the series (various bookings, May 29-June 27, 1970), see here