|

| The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, ca. 1969 |

The Family Dog on The Great Highway, 660 Great Highway, San Francisco, CA

The

Family Dog was a foundation stone in the rise of San Francisco rock,

and it was in operation in various forms from Fall 1965 through the

Summer of 1970. For sound historical reasons, most of the focus on the

Family Dog has been on the original 4-person collective who organized

the first San Francisco Dance Concerts in late 1965, and on their

successor Chet Helms. Helms took over the Family Dog in early 1966, and

after a brief partnership with Bill Graham at the Fillmore, promoted

memorable concerts at the Avalon Ballroom from Spring 1966 through

December 1968. The posters, music and foggy memories of the Avalon are

what made the Family Dog a legendary 60s rock icon.

In the Summer of 1969, however, with San Francisco as one of the fulcrums of the rock music explosion, Chet Helms opened another venue. The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, on the Western edge of San Francisco, was only open for 14 months and was not a success. Yet numerous interesting bands played there, and remarkable events took place, and they are only documented in a scattered form. This series of posts will undertake a systematic review of every musical event at the Family Dog on The Great Highway. In general, each post will represent a week of musical events at the venue, although that may vary slightly depending on the bookings.

If anyone has memories, reflections, insights, corrections or flashbacks about shows at the Family Dog on the Great Highway, please post them in the Comments.

|

| 660 Great Highway in San Francisco in 1967, when it was the ModelCar Raceway, a slot car track |

The Edgewater Ballroom, 660 Great Highway, San Francisco, CA

As early as 1913, there were rides and concessions at Ocean Beach in San Francisco, near the Richmond District. By 1926, they had been consolidated as Playland-At-The-Beach. The Ocean Beach area included attractions such as the Sutro Baths and the Cliff House. The San Francisco Zoo was just south of Playland, having opened in the 1930s. One of the attractions at Playland was a restaurant called Topsy's Roost. The restaurant had closed in 1930, and the room became the Edgewater Ballroom. The Ballroom eventually closed, and Playland went into decline when its owner died in 1958. By the 1960s, the former Edgewater was a slot car raceway. In early 1969, Chet Helms took over the lease of the old Edgewater.

|

| One

of the only photos of the interior of the Family Dog on The Great

Highway (from a Stephen Gaskin "Monday Night Class" ca. October 1969) |

The Family Dog On The Great Highway

The Great Highway was a four-lane road that ran along the Western edge of San Francisco, right next to Ocean Beach. Downtown San Francisco faced the Bay, but beyond Golden Gate Park was the Pacific Ocean. The aptly named Ocean Beach is dramatic and beautiful, but it is mostly windy and foggy. Much of the West Coast of San Francisco is not even a beach, but rocky cliffs. There are no roads in San Francisco West of the Great Highway, so "660 Great Highway" was ample for directions (for reference, it is near the intersection of Balboa Street and 48th Avenue). The tag-line "Edge Of The Western World" was not an exaggeration, at least in American terms.

The Family Dog on The Great Highway was smaller than the Bill Graham's old Fillmore Auditorium. It could hold up to 1500, but the official capacity was probably closer to 1000. Unlike the comparatively centrally located Fillmore West, the FDGH was far from downtown, far from the Peninsula suburbs, and not particularly easy to get to from the freeway. For East Bay or Marin residents, the Great Highway was a formidable trip. The little ballroom was very appealing, but if you didn't live way out in the Avenues, you had to drive. As a result, FDGH didn't get a huge number of casual drop-ins, and that didn't help its fortunes. Most of the locals referred to the venue as "Playland."

- For a complete list of Family Dog shows (including FDGH), see here

- For the previous entry (September 15-26, 1969) see here

- For a summary and the link to the most recent entries in this series, see here

By October of 1969, the Family Dog on The Great Highway appears to have been surviving week to week. While they had begun in June with regular weekend bookings featuring headline acts, with albums and status, the ranking of the performers had declined. While the Family Dog was a nexus for interesting creative types, the lack of money meant that working bands only played the Dog as a last resort. For much of September, the venue had been more like a community center, with different artistic groups using it for their own events. The community focus was admirable, but financially unsustainable.

September 30, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen/Clover/Deluxe/Flying Circus Tom Mix Memorial Ball presented by the 13th Tribe (Tuesday)

On Tuesday, the Family Dog presented "The Tom Mix Memorial Ball," which was promoted as a country and western show. The 13th Tribe were a local organization that I recognize from contemporary posters, but I don't know anything about them. Based on their name, they sound like some sort of commune that promoted local rock events, but that is just my own speculation.

Today we think of Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen as an established Bay Area band, and of course they would go on to release several albums on a variety of labels. In September of 1969, however, the band was newly-arrived in Berkeley from Ann Arbor, MI. The band's knowing mixture of honky-tonk country, Western Swing and songs about weed would find a comfortable home in the Bay Area, but their first album was still two years in the future. The Airmen, in fact, had played the Family Dog at least three times already in August, including opening for the Grateful Dead, but they had hardly played anywhere else save for weeknights at a tiny Berkeley club on University and San Pablo called Mandrake's.

|

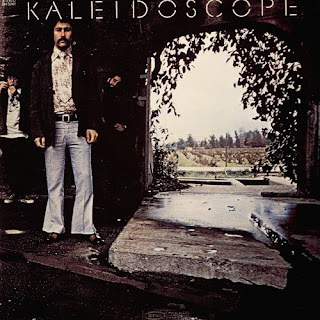

| Clover's debut album was released on Fantasy Records in 1970 |

Clover and Flying Circus were Mill Valley bands, sharing a rehearsal hall and equipment. Clover, a country rock quartet with an R&B edge, would get signed by Fantasy Records, and would release their debut album on Fantasy Records in 1970. Clover had a complicated, up-and-down career, releasing four excellent but hardly-noticed albums. Fortunately, however, they were noticed by Nick Lowe, so they ended up backing Elvis Costello on My Aim Is True. Lead (and pedal steel) guitarist John McFee would end up in the Doobie Brothers--he's still in the band--and the various members of Clover mostly went on to musical successes in the later 70s. But in the late 60s, they were just a struggling quartet, with McFee on lead and pedal steel, Alex Call on vocals and guitar, John Ciambotti on bass and Mitch Howie on drums.

Flying Circus had existed in some form since 1966, and had released a few singles, but they had undergone numerous personnel changes. By '69, Flying Circus' lead guitarist was Bob McFee, brother of John. Flying Circus developed a following around the North Bay, but they never got as far even as Clover. Still, by all accounts they were a pretty good band.

Deluxe is unknown to me.

October 1, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Maximum Speed Limit/Alligator/Old Davis/Straight Phunk (Wednesday)

Wednesday was listed as "New Band Night." The Fillmore West had a similar long-running program on Tuesday nights. Maximum Speed Limit was a Berkeley band, but I don't know anything else about them. Alligator is unknown to me, as is Straight Phunk. Old Davis was a Redwood City band. By 1970, teenage San Mateo guitarist Neal Schon was a member of Old Davis, but I don't think he was in the group yet.

October 3-5, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Kaleidoscope/Charlie Musselwhite/Congress Of Wonders (Friday-Sunday)

After some clearly sub-par weeks, the Family Dog had some relatively established draws on the first weekend of October. All three bands were not only established Avalon acts, they had played the Family Dog on The Great Highway before as well. Headliners Kaleidoscope had played back in June, Charlie Musselwhite had played in July, and Congress of Wonders had played in June, July and August.

The Kaleidoscope were from Los Angeles, and they were decades ahead of their time. They had pretty much invented World Music, and pretty much no one was ready for it. In June 1969, the band had released their third album on Epic, Incredible! Kaleidoscope. It lived up to its name. While the band was still fronted by guitarist/multi-instrumentalist David Lindley, multi-instrumentalist Solomon Feldthouse and organist/multi-instrumentalist Chester Crill, they had a new rhythm section. Paul Lagos was the drummer and Stuart Brotman played bass. Anyone who ever got to see the band live was lucky.

The Avalon had had a reputation for finding cool bands before anyone else. If Helms had booked a band at the Avalon, and they got good notices, Bill Graham wasn't far behind, offering them more money and a higher profile. Kaleidoscope had played the Avalon various times since early '67, and while they were too far ahead of their time for most listeners, other musicians just about lost their minds. When Kaleidoscope had played the Avalon on May 24-26, 1968 (booked between the Youngbloods and the Hour Glass, with Duane and Gregg Allman), for example, the Yardbirds were booked at the Fillmore West the same weekend. Jimmy Page has told the story of taking time out between sets to walk the 12 blocks over to the Avalon just to catch the Kaleidoscope, and then walking the 12 blocks back to play his late night set with the Yardbirds.

Charlie Musselwhite had been born in Mississippi and moved to Memphis, and then ultimately to Chicago. He was one of a small number of white musicians in Chicago (including Nick Gravenites, Paul Butterfield, Mike Bloomfield, Elvin Bishop and a few others) who had stumbled onto the blues scene by themselves. A Chicago club regular, Musselwhite eventually recorded an album for Vanguard in 1967 called Stand Back, which started to receive airplay on San Francisco’s new underground FM station, KMPX-fm. Friendly with the Chicago crowd who had moved to San Francisco, his band was offered a month of work in San Francisco in mid-1967, so Musselwhite took a month’s leave from his Chicago day job and stayed for a couple of decades.

Musselwhite had released his second album on Vanguard, Stone Blues, in 1968. Sometime in 1969, Vanguard released Tennessee Woman. Musselwhite was a regular on the Bay Area club scene, and had played the Fillmore and Avalon as well. In Chicago, Musselwhite had been just one of many fine blues acts, but in the Bay Area he stood out. Musselwhite had been a regular at the Avalon Ballroom, but he had never graduated to the Fillmore or Fillmore West. He was excellent live, but a Musselwhite show was still not going to be a must-see event for local rock fans.

Congress of Wonders were a comedy trio from Berkeley, initially from the UC Berkeley drama department and later part of Berkeley’s Open Theater on College Avenue, a prime spot for what were called “Happenings” (now ‘Performance Art’). The group had performed at the Avalon and other rock venues.

Ultimately a duo, Karl

Truckload (Howard Kerr) and Winslow Thrill (Richard Rollins) created two

Congress of Wonders albums on Fantasy Records (Revolting and Sophomoric). Their pieces

“Pigeon Park” and “Star Trip”, although charmingly dated now, were staples of

San Francisco underground radio at the time ("Pigeon Park" is from their 1970 debut album Revolting).

The duo was one of a number of comedy troupes to take advantage of the

recording studio, overdubbing voices and sound effects in stereo, to

enhance the comedy.

What Happened?

We actually know a little bit about this weekend. In an interview with music scholar Jake Feinberg, David Lindley described sitting upstairs at the Family Dog and listening to Charlie Musselwhite's band. Lindley and his fellow band members thought that Musselwhite had an innovative saxophonist, somewhat out of character. They went down to the stage to discover that Musselwhite's band featured the unique steel guitarist Freddie Roulette. Roulette (b. 1939) was from New Orleans, but had moved to Evanston, IL (a Chicago suburb, and had learned to jam the blues on a lap steel guitar. Lindley was completely fascinated with Roulette's approach to the instrument. Roulette had played with blues guitarist Earl Hooker since 1965, and he would move to San Francisco to play with Musselwhite. Roulette had played on the Tennessee Woman album. Lindley's innovative steel guitar playing with Jackson Browne and others is world famous, and it seems that Roulette was a foundational building block for him.

While just a fragmentary memory, Lindley's recollection is actually more than we usually hear about Family Dog on The Great Highway shows.

For the next post in this series (October 7-16, 1969, various bands), see here

No comments:

Post a Comment