|

| The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, ca. 1969 |

The Family Dog on The Great Highway, 660 Great Highway, San Francisco, CA

The

Family Dog was a foundation stone in the rise of San Francisco rock,

and it was in operation in various forms from Fall 1965 through the

Summer of 1970. For sound historical reasons, most of the focus on the

Family Dog has been on the original 4-person collective who organized

the first San Francisco Dance Concerts in late 1965, and on their

successor Chet Helms. Helms took over the Family Dog in early 1966, and

after a brief partnership with Bill Graham at the Fillmore, promoted

memorable concerts at the Avalon Ballroom from Spring 1966 through

December 1968. The posters, music and foggy memories of the Avalon are

what made the Family Dog a legendary 60s rock icon.

In the Summer of 1969, however, with San Francisco as one of the fulcrums of the rock music explosion, Chet Helms opened another venue. The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, on the Western edge of San Francisco, was only open for 14 months and was not a success. Yet numerous interesting bands played there, and remarkable events took place, and they are only documented in a scattered form. This series of posts will undertake a systematic review of every musical event at the Family Dog on The Great Highway. In general, each post will represent a week of musical events at the venue, although that may vary slightly depending on the bookings.

If anyone has memories, reflections, insights, corrections or flashbacks about shows at the Family Dog on the Great Highway, please post them in the Comments.

|

| 660 Great Highway in San Francisco in 1967, when it was the ModelCar Raceway, a slot car track |

The Edgewater Ballroom, 660 Great Highway, San Francisco, CA

As early as 1913, there were rides and concessions at Ocean Beach in San Francisco, near the Richmond District. By 1926, they had been consolidated as Playland-At-The-Beach. The Ocean Beach area included attractions such as the Sutro Baths and the Cliff House. The San Francisco Zoo was just south of Playland, having opened in the 1930s. One of the attractions at Playland was a restaurant called Topsy's Roost. The restaurant had closed in 1930, and the room became the Edgewater Ballroom. The Ballroom eventually closed, and Playland went into decline when its owner died in 1958. By the 1960s, the former Edgewater was a slot car raceway. In early 1969, Chet Helms took over the lease of the old Edgewater.

|

| One

of the only photos of the interior of the Family Dog on The Great

Highway (from a Stephen Gaskin "Monday Night Class" ca. October 1969) |

The Family Dog On The Great Highway

The

Great Highway was a four-lane road that ran along the Western edge of

San Francisco, right next to Ocean Beach. Downtown San Francisco faced

the Bay, but beyond Golden Gate Park was the Pacific Ocean. The aptly

named Ocean Beach is dramatic and beautiful, but it is mostly windy and

foggy. Much of the West Coast of San Francisco is not even a beach, but

rocky cliffs. There are no roads in San Francisco West of the Great

Highway, so "660 Great Highway" was ample for directions (for reference,

it is near the intersection of Balboa Street and 48th Avenue). The

tag-line "Edge Of The Western World" was not an exaggeration, at least

in American terms.

The Family Dog on The Great Highway was

smaller than the Bill Graham's old Fillmore Auditorium. It could hold up

to 1500, but the official capacity was probably closer to 1000. Unlike

the comparatively centrally located Fillmore West, the FDGH was far from

downtown, far from the Peninsula suburbs, and not particularly easy to

get to from the freeway. For East Bay or Marin residents, the Great

Highway was a formidable trip. The little ballroom was very appealing,

but if you didn't live way out in the Avenues, you had to drive. As a

result, FDGH didn't get a huge number of casual drop-ins, and that

didn't help its fortunes. Most of the locals referred to the venue as

"Playland."

Chet Helms had opened the Family Dog at 660 Great Highway to much fanfare on June 13, 1969, with a packed house seeing the Jefferson Airplane and The Charlatans. One of the goals was that the Dog would feature mostly San Francisco bands and a variety of smaller community events and groups. Since so many San Francisco bands were successful, and had record contracts, this didn't confine the venue to obscurity. A lot of great bands played the Family Dog in 1969, but the distant location and the gravitational pull of major rock events hosted elsewhere in the Bay Area kept the Family Dog isolated. We know only the most fragmentary bits about music played, events and audiences throughout the year. Despite the half-year of struggle, Helms had kept the Family Dog on The Great Highway afloat. He had entered the new year of 1970 with a new plan.

- For a complete list of Family Dog shows (including FDGH), see here

- For the previous entry (May 1-24, 1970 various) see here

- For a summary and the link to the most recent entries in this series, see here

May 29-31, 1970 Family Dog on the Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Indian Music Festival featuring Ali Akbar Khan, Indranil Bhattacharya, Zakir Hussain (Friday-Sunday)

Indian classical music had been known in the West since Ravi Shankar's album Three Ragas, released on World Pacific Records in 1956. By the mid-60s, jazz musicians like John Coltrane and rock musicians such as Eric Clapton had discovered the music. George Harrison had helped introduce the sitar, Ravi Shankar, and Indian music to the wider pop music audience. Indian music was important in both rock and jazz because it influenced players like Coltrane and Clapton, even when the wider public was only vaguely aware of it. In the Bay Area, the Ali Akbar Khan School of Music in Oakland had been an important locus for teaching and learning since the 1960s. As it happened, Family Dog soundman Owsley Stanley was not only a huge admirer of Indian music, he was intimately connected to the Ali Akbar Khan School as well. The School had been based in a big house on Ascot Drive in the Oakland hills.

In her recent book Owsley And Me: My LSD Family, Rhoney Gissen described the house in Ascot Drive in some detail. Originally it had been rented by Ali Akbar Khan school of music.

Indian music gave me clarity, so I drove to the Ali Akbar Khan School Of Music, situated in a beautiful Spanish-style multilevel house with arts-and-crafts detailing in the secluded hills of Oakland, southeast of Berkeley. While I was listening to a morning raga played by Khansahib with Vince Delgado on tabla, it occurred to me that this place would be perfect for Bear. With all the rooms and levels, he could live here with any member of the Grateful Dead family. Ramrod had already agreed to live with Bear when he moved [p166]Since the School was moving at month's end, Owsley was intrigued enough to visit:

We walked around the house and there was a swimming pool and a separate entrance in the back. Stately trees reached beyond the third floor. We went back inside which was atop a long stairway from the front door.Bear eventually agrees, and Rhoney gets Bear to let Ali Akhbar Khan and his students to open for the Grateful Dead in Berkeley (at the Berkeley Community Theater on September 20, 1968) in return for letting Owsley take over the lease.

"Look, Bear, I can stand at the top of the stair and see who's coming."

"Yes, but you can't see the front door from any of the windows." [p.167]

At the end of the Summer of 1968, when the Indian musicians moved out of the house in the Oakland hills, Bear moved in. Betty and Bob Matthews took the downstairs apartment, and Ramrod moved into the bedroom next to Bear's. Weir camped out in the living room. [p168]Owsley lived in the Ascot Drive house until his incarceration in July of 1970. The Ali Akbar Khan School of Music moved to San Rafael, and seems to be still going strong today.

I'm not sure who booked the Indian music weekend at the Family Dog, or to put it another way, I'm not sure who took the risk and whether it was profitable. The program featured Ali Akbar Khan (sarod), Indraril Bhatticharva (sitar) and Zakir Hussain (tabla). Nonetheless, Owsley was still Owsley, and not only did he act as soundman, but he taped it as well. In 2020, the Owsley Stanley Foundation released some performances from the first night (May 29, 1970).

June 7, 1970 Family Dog on the Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: The One Festival (Sunday)

Our only trace of this weekend's events was an ad in the SF Good Times for a Sunday afternoon lecture called "The One Festival." With no Friday or Saturday night rock show (that I am aware of), it seems pretty likely that the Family Dog on The Great Highway was effectively just another hall for rent.

The names on the poster are all Indian or South Asian "gurus," save for "Sufi Dancers," and Indradril Bhattacharva, noted as a member of the Ali Akbar Khan college of music, and Stephen Gaskin. Gaskin, a popular literature instructor at San Francisco State who had held "Monday Night Class" events at the Family Dog in the Fall, presented a variety of Indian and Asian philosophies, so he actually fit in with the rest of the bill. In modern terms, this would be seen as a "Self-Help" or "Human Potential" seminar. Hippies were inclined to think India was a purer source for spiritual enlightenment than the West.

[update 20241016] For some color footage showing the interior of the Family Dog, see this clip from a film on Swami Satchidananda.

June 13, 1970 Family Dog on the Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: First Anniversary at the Beach Party (Saturday)

June 13, 1970 was indeed the first anniversary of the opening of the Family Dog on The Great Highway. On June 13, 1969, the Dog had opened at the beach with the Jefferson Airplane and a jam-packed house. By 1970, there was only the vaguest mention of an event, with no bands listed. It was probably an open house of some sort. The Family Dog on The Great Highway had fallen far in the preceding year, and I'm sure no one thought there would be a second anniversary.

June 17, 1970 Family Dog on the Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Michael Bloomfield & Marin Music Band/Charles Musselwhite Blues Band/Sandy Bull St Jacques Benefit for the Porcupine Family Inc drug treatment program (Wednesday)

Mike Bloomfield had been America's first genuine guitar hero, and he was a truly great musician. He had moved to San Francisco in 1967 to form the Electric Flag. When Bloomfield had left the Flag in 1968, he had a brief flash of solo stardom with Al Kooper and Super Session, but he largely limited himself to playing small local gigs. He had a rotating lineup of fine players in support, but he never rehearsed. So while Bay Area rock fans all agreed, in principle, that Bloomfield was a legend, his appearances were hardly events. Presumably, he was backed at this show by the likes of Nick Gravenites, Mark Naftalin, John Kahn and Bob Jones (his "first-call" team), but we don't know that for certain. Bloomfield had headlined a weekend at the Dog back on August 15-16, 1969.

As far as records went, Bloomfield's most recent album was It's Not Killing Me, released on Columbia in 1969. It wasn't bad, but it wasn't really memorable, either. Bloomfield was backed by the crew who made up his rotating stage band, and they were all good, but the material was weak.

Charlie Musselwhite, from Memphis via Chicago, had been the top white harmonica player in the mid-60s in Chicago, when Bloomfield had been part of the Butterfield Blues Band. Musselwhite, too, had moved to San Francisco in '67 and had played the Avalon and other ballrooms regularly. His current album would have been Memphis, Tennessee, on Paramount, featuring the unique steel guitarist Freddie Roulette. I don't know if Roulette was still in Musselwhite's band. By the end of 1970, his group would be fronted by a teenage guitarist from Ukiah, CA named Robben Ford, who would go on to a brilliant career himself.

Sandy Bull was a solo guitarist, a unique and remarkable

performer whose elaborate fingerpicking was enhanced by various

electronic looping effects. Although appealing to a rock audience, more

or less, Bull was the type of performer whose audience remained seated.

He had played the Bay Area many times over the years, usually at The Matrix. He had played the Family Dog a month earlier (May 15-16). At this time, his most recent album would have been E Puribus Unum, released on Vanguard the previous year. Bull had played all the instruments himself, and the music was hardly rock.

June 19-21, 1970 Family Dog on the Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Flying Burrito Brothers/Cat Mother & the All Night Newsboys/Rhythm Dukes with Bill Champlin and Jerry Miller (Friday-Sunday)

This June weekend was the last time that the Family Dog presented a multiple bill featuring a touring act and some local bands for a weekend. There were a few more rock concerts in July and August, but none of those suggested that there was anything ongoing, just concert opportunities. This booking was the last sign of the Family Dog as an ongoing concern.

The Flying Burrito Brothers had released their second A&M album in May 1970, Burrito Deluxe. The band's 1969 debut had gotten extraordinarily good reviews, but the Burritos had been a sloppy and indifferent live band. Gram Parsons, in particular, refused to tour much, as he was determined to hang out in Los Angeles with the Rolling Stones. Parsons was a Burrito for the Burrito Deluxe album, but he was fired by Chris Hillman before touring had started in June. Parsons was increasingly erratic, and in any case wasn't up for the promotional effort. The Burritos had never played the Fillmore West, but they had played the Family Dog, so that may account for why they were booked at the Dog instead.

During this brief period, the Flying Burrito Brothers were just a quartet. Chris Hillman was the primary vocalist and bassist, with Bernie Leadon on lead guitar and harmonies. The legendary Sneaky Pete Kleinow remained on pedal steel guitar, and ex-Byrd Michael Clarke remained the drummer. The Burritos knew they needed a fifth member, and toyed with adding ex-Byrd Gene Clark, who actually played a few gigs. It's not impossible Gene Clark was at one or all of the Family Dog gigs. Clark, too, was an erratic character, and ultimately Rick Roberts would join the Burritos later in 1970.

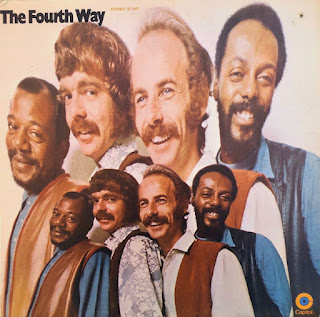

|

| The Rhythm Dukes at The Family Dog on The Great Highway, sometime in 1970. (L-R) Bill Champlin, John Oxendine, Jerry Miller. |

The Rhythm Dukes had formed in the Santa Cruz mountains in 1969, and had played the Family Dog on The Great Highway on December 12-14, 1969. Originally the band had featured two former members of Moby Grape, lead guitarist Jerry Miller and ex-drummer Don Stevenson (who switched to guitar). They were supported by bassist John Barrett and drummer Fuzzy Oxendine, formerly of the 60s group Boogie. The band was often billed as Moby Grape, and Stevenson had left by the end of Summer '69. The Rhythm Dukes carried on as a trio, finally adding two more members by December (saxophonist Rick Garcia and keyboardist Ned Torney).

By January, however, the two extra members had left, to be replaced by Bill Champlin from the Sons. By early 1970, despite a loyal Bay Area following and two excellent Capitol albums, the Sons of Champlin were frustrated and broke and they decided to go "on hiatus." Effectively that meant they were breaking up, although they continued to finish an album they owed Capitol (released in 1971 as Follow Your Heart). The Sons had concert obligations through February of 1970, so while Bill Champlin played a few gigs with the Rhythm Dukes, he was also finishing up with the Sons. By March, the Sons had stopped performing--that didn't last long, but it's another story--and Bill was full time with the Rhythm Dukes and Jerry Miller.

We have a photo of Bill Champlin with the Rhythm Dukes from the Family Dog, although the exact date is unknown. Champlin played organ and rhythm guitar with the Dukes, and was the principal lead singer, although Jerry Miller was also a fine vocalist. Our only tape of this era of the Rhythm Dukes was privately released 2005 cd of some demo tapes from April 1970, (called Flash Back) but they were plainly an excellent live band. This was the third weekend that the Rhythm Dukes with Champlin would play the Family Dog on The Great Highway, but this seems to be the last booked show I can find by the band. Both Miller and Champlin would return to their natural homes (Moby Grape and The Sons) later in 1970.

Greenwich Village band Cat Mother and The All-Night Newsboys had formed in 1967. By 1969, they had been signed by Michael Jeffery, the manager of Jimi Hendrix. Hendrix had even produced the band's debut album on Polydor, The Street Giveth and The Street Taketh Away. Thanks to the Jeffery connection, Cat Mother got to open for Hendrix and a number of other high profile events. Cat Mother even had a minor hit in late '69, with medley of oldies called "Old Time Rock And Roll." In fact, the band's sound was more country-folk oriented, but they were versatile musicians.

June 23-25, 1970 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: 12 bands (Tuesday-Thursday)

A note in the June 22 San Francisco Examiner mentioned that "12 bands" would play the Family Dog from Tuesday through Thursday. I have no other information, nor any real indication that any of these events were held.

Osceola, Cleveland Wrecking Co, Mendelbaum, Sawbucks (w/Ronnie Montrose) and Cat Mother have been mentioned elsewhere in the FDGH saga.

Brown Rice, Bay Break, Cantrel Justantine, Orion, Chambray and Backwater Rising are unknown to me.

The Aliens were perhaps San Francisco's first Latin rock group, dating back to 1965. Then Mission HS teenager Carlos Santana occasionally sat in with him, and Chepito Areas was a member of The Aliens around 1967-68.

Loose Gravel was led by ex-Charlatan guitarist Michael Wilhelm.

The most interesting name on the bill is Children Of Mu, who very well may be the legendary psychedelic surf pioneer band featuring Merrell Fankhauser and Jeff Cotten.

The only indication of an event on the weekend of June 25-27 was that the Hare Krishna was going to have a big public dinner at the Family Dog on The Great Highway on Sunday, June 27. The Krishna were having a big "happening" in Golden Gate Park over the weekend, and it would culminate with a big dinner. Whether the Hare Krishnas had other, private events at the Dog during the weekend is not mentioned.

The Family Dog on The Great Highway was just a venue for rent, with no viable economic program. It was only a matter of time before it would shut down.

For the next post in the series (The Kinks, June 30-July 1, 1970) see here