On July 8, 1972 there was a huge multi-act rock festival at Pocono International Raceway in Pennsylvania. Pocono Speedway, though in rural Long Pond, was nonetheless in driving distance for a huge population of teenagers in greater Pennsylvania and parts of Northern New Jersey. Pocono Raceway was less than an hour from Scranton, Allentown and Nazareth, and about 90 minutes from the suburbs of Philadelphia and Newark. There was a huge teenage population of suburban rock fans in all those cities with access to their parent's cars. 120,000 fans showed up to see Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Faces, Humble Pie, Three Dog Night and and numerous other bands, completely overwhelming the facility.

In the early 1970s, the live rock concert business was expanding at record speed. There was a frantic search to re-purpose existing spaces for large rock concerts. In the 60s, rock festivals had mostly been on empty agricultural land, but the concerts inevitably ended with most fans getting in for free, defeating the purpose of the enterprise in the first place. Auto Racing tracks, which had thrived in the United States after World War 2, seemed to offer an excellent option: they were self-contained venues with water, power and parking, designed to handle a weekend of noisy activities for a substantial crowd.

The biggest rock concert of the decade would be on July 28, 1973 at the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Course in New York, where 600,000 showed up to see the Allman Brothers, the Grateful Dead and The Band. Of course, only about 150,000 of those fans paid, but it was enough to make the event profitable. That paid attendance record was broken the next year when Emerson, Lake and Palmer and Deep Purple headlined the "California Jam" at the Ontario Motor Speedway in Los Angeles on April 6, 1974, when at least 168,000 of the 200,000 in attendance bought a ticket. This record, in turn was broken at "Cal Jam 2," held four years later at OMS, when at least 175,000 paid. So rock concerts at auto racing tracks could be big business, indeed, and made for an intriguing proposition.

Intriguing, yes--but it didn't really work out. I looked into this phenomenon at length, but I limited my scope to a post about Ontario Speedway and one about Grateful Dead concerts, just to keep the analysis comprehensible. But there were other events as well, and I am attempting to capture all the major ones. The July 8, 1972 concert at Pocono International Raceway was not the first or last attempt to put on a rock concert at the Long Pond, PA track in the Pocono Mountains, but it was the only one that actually happened. This post will take a look at the brief intersection between Pocono Raceway and the rock concert world, as well as using the concert bill as a snapshot of bands touring the United States that Summer.

Rock Concert Economics: 1972

In 1972, there was a huge audience for live rock music, but that audience was young, and without much ready cash. Also, since rock music stood for "rebellion," the most popular of rock music attractions were vulnerable to the complaint that they were charging "too much" for tickets. The inevitable result of these pressures was that popular rock bands put on concerts in larger and larger venues, instead of charging more at smaller places. By 1972, the most popular bands were selling out basketball arenas with capacities of 12,000 or more, even in so-called "secondary" markets. Ticket prices were reasonable, around 4 or 5 dollars usually, but the total number of tickets sold was larger than ever.

By the early 70s, multi-act "Festival" shows had mostly been financial debacles and public relations disaster, and it wasn't just Altamont: check out the saga of the "Erie Canal Soda Pop Festival" in Griffin, Indiana on Labor Day weekend of 1972. Smart promoters were looking for other workable venues, and race tracks re-appeared on the horizon. An interesting thing to consider about auto racing was that--because of the noise--they had to generally be well outside any populated areas, but still within driving distance of a lot of potential fans. At the same time, since fans had to drive a fair amount to get there, a race track generally offered a whole slew of events at a race weekend, not just a headline race. These economics pretty much defined multi-act rock concerts, just for a different, younger fan base.

Thus, one of the intriguing solutions for hosting giant rock

festivals was to use facilities designed for auto racing. Race tracks

were usually somewhat removed from urban areas while still being near

enough to civilization to attract a crowd. Auto races themselves were

noisy, and major race events tended to occur just a few times a year and

last an entire weekend, just like a rock festival. Since race tracks

were permanent facilities, they generally had fences, bathrooms, water,

power and parking, so in many ways they would seem like ideal venues for

huge rock events. Indeed, some of the major rock events of 1969 and 1970 were held at race tracks (such as the Atlanta Pop Festival, the Texas Pop Festival and the disastrous Rolling Stones concert at Altamont).

I looked at some of the history and economic dynamics of Auto Racing tracks as Rock Concert sites in another post, although for purposes of scale I focused on the Grateful Dead. Generally speaking, while auto racing had been popular since the invention of the automobile, it was horse racing that had been hugely popular in cities and county fairs throughout the United States, long before cars were invented. However, after WW2, when the GIs returned and economy boomed, America moved from its rural roots to a more urban and suburban universe, and the automobile became a more important part of everyone's life. A national boom in the popularity of auto racing corresponded with a slow decline in the popularity of horse racing.

By the early 1960s, numerous custom-built facilities served the hugely popular auto racing industry, with oval tracks (for NASCAR and "Indianapolis" cars in the South and Midwest), road courses (for sports cars on both coasts) and dragstrips (nationwide). These facilities were ready made for rock concerts, but there were some huge cultural divides. With a middle-class family audience for auto races, along with their Dow Jones Industrial sponsorship from major companies, racetrack promoters were neither tuned into nor inclined to sponsor long-haired outlaw rock concert events flaunting nudity and drugs.

Pocono Mountains Recreational AreaThe Pocono Mountains area had long been the recreational and resort area for Philadelphia and Northern Pennsylvania, as well as Northern New Jersey and Southern New York state. The beautiful Poconos were an attractive place to ski, swim, hunt, fish or just relax. There were numerous hotels and resorts catering to tourists and families. A huge population of people were within a few hours drive. An auto racing track in the Mountains made a lot of sense. The area was familiar to a huge population, and a race track also made a good tourist destination.

Work on the Pocono Raceway had actually begun in 1965, but the first stage of the facility was not completed until October 1968. At first Pocono International Raceway comprised a three-quarter mile oval and a drag strip (which was to double as the main straight for the full, 2.5-mile 'tri-oval'). A 1.8-mile road course was added in 1969 and in early 1970 the work on the full-sized oval was started. The track was financed by a successful Philadelphia dentist (Joe 'Doc' Mattioli), who quit his prosperous practice one day in 1960 in order to enjoy a more adventurous life, along the way amassing a small fortune in property deals in the Poconos.

The early racing events were low-key. The first race on the oval was held in May, 1969. IMSA's debut race was held on the oval on October 19, 1969 (for Formula Ford cars), there was an SCCA National road race in March 1970, and a 200-lap (150 mile) USAC Stock Car race in July 1970. The first race on the full 2.5 mile oval was the Schaefer 500, on July 3, 1971, a 500-mile race won by local hero Mark Donohue, who just barely beat out Joe Leonard and AJ Foyt.

Spring 1970

The first attempt to hold a rock festival at Pocono Raceway was in Spring, 1970. At this time, although the full Indy-car 2.5 mile oval was under construction, the racetrack was still essentially a regional facility. Nonetheless, Electric Factory Productions, the biggest rock promoter in Philadelphia and the surrounding region, enquired whether Pocono Raceway could be rented to stage a rock festival. In 1969, the Electric Factory had held a very successful three day festival at horse racing track in Atlantic City, on August 1-3 (two weekends before Woodstock). The crowd in New Jersey had been well-behaved, the track had bathrooms, lights and power, and the basic design of the track both controlled access and ensured that it would never turn into an unprofitable free concert.

Electric Factory founder Larry Magid told the story of the company's efforts to stage a festival in 1970 in his memoir Electric Factory: My Soul's Been Psychedelicized (Larry Magid with Robert Huber 2011: Temple U Press p.68):

The Atlantic City Pop Festival, unlike the three days in the mud on Yasgur's farm in upstate New York, made money and stayed organized. Nevertheless, it was Woodstock's immediate infamy that established the public image of the outdoor rock festival and associated it with danger and mayhem.

[Magid's partner] Allen Spivak kept trying to replicate the success of the A.C. Pop Festival, pursuing an outdoor site in Pennsylvania at Pocono Raceway or Bushkill Falls. As far as the locals near Pocono Raceway were concerned, a three-day show meant a half million people trampling in. A community meeting at a firehouse became so crazy, so threatening, that Allen's attorney told him, "We have to get the hell out of here. We're going to be lynched."

The Electric Factory attempted to stage their festival over six days at the Wallpack Center in New Jersey, just across the Delaware River from Pennyslvania, but it was blocked by a judge. In subsequent years, the Electric Factory would limit their largest events to football stadiums. A day with 60,000 people was far more manageable than multiple days with huger multiples of fans.

|

| Mark Donohue won the first IndyCar race at Pocono Speedway in 1971 for Penske Racing, with the new McLaren M16A-Offy |

Pocono International Raceway

The full 2.5 mile Pocono was finally completed in June 1971. The Schaefer 500, 200 laps and 500 miles, was held on July 4, 1971. Per the track history:

Workers were still applying the final touches when the USAC Indycar Championship rolled into the facility for the first 500 mile race, sponsored by the Schaefer brewing company. On 19 June 1971, Rose Mattioli, Doc's wife who was ever present at Pocono, cut the ribbon to open the track for practice. Two hours later Jim Malloy's Eagle-Ford made a few, tentative laps for the benefit of the television cameras. Official qualifying trials for the 500 took place on the weekend of 26-27 June, Mark Donohue qualifying on pole in a Penske-entered McLaren M16-0ffenhauser.

The race itself was on 4 July and Donohue was in strong form, leading the majority laps before being challenged in the final stages by the Colt-Ford of Joe Leonard. A late yellow flag caution period bunched the field and when the green 'all-clear' was given, the Colt flashed by the McLaren through Turn Two. For three laps Leonard remained ahead, but he could not fend off the blue McLaren when Donohue surged by on the main straight to take the win by just 1.6 seconds after 500 miles of close racing. The crowd went wild with excitement, invading the pit area after the race.

The initial Schaefer 500 had been a success, and the Schaefer Beer company re-upped to sponsor the 1972 500 mile race. Pocono Raceway was a new facility, however, and would have been looking for other sources of revenue. There would not be a NASCAR race there until 1974. So it seems likely that when another rock promoter offered the track a lucrative opportunity to host a rock festival, they must have got a positive response.

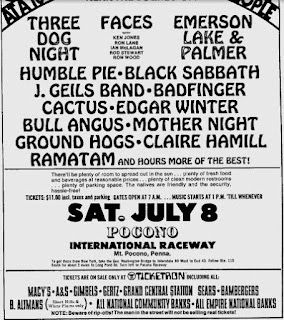

July 8, 1972 Pocono International Raceway, Long Pond, PA: Three Dog Night/Faces/Emerson, Lake & Palmer/Humble Pie/Black Sabbath/J. Geils Band/Badfinger/Cactus/Edgar Winter/Bull Angus/Mother Night/Groundhogs/Claire Hammill/Ramatam (Saturday) Concert 10 Presents

Concert production at the Pocono festival was handled by Concert 10, Inc. First time concert producers Irving Reiss, vice president of the Candygram Company, and attorney George Charak put US$250,000 in escrow to avoid problems paying the artists faced by previous festivals. Legend has it that 66 people were hired from Bill Graham's road crew in Dallas to maintain the sound reinforcement system. Bill Graham did not, in fact, have a "road crew" in Dallas or anywhere else. Still, "Bill Graham" was the gold standard of concert promotion, thanks to the Fillmores East and West, so invoking his name was a sign that, presumably, the promoters had hired some people with rock concert presentation experience.

Another bit of the legend was that "300 security people backed by University karate clubs maintained order." This, too, was absurd if you actually stop to think about it, but its the kind of things promoters said to reassure locals: we escrowed money, we hired Bill Graham's crew, we hired college students who know karate. All of those claims evoke the likelihood of success.

The Festival was a success. A big success. Too big a success. Plus it poured with rain. The promoters assessment of the potential audience was correct. Kids came from everywhere. It's worth noting that while the three headliners were popular, none of them could have headlined a stadium concert by themselves. Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Three Dog Night and Rod Stewart and The Faces all had popular albums, and varying degrees of hit singles on the radio. But they weren't like the Rolling Stones. Young people from the region just wanted to go to a big outdoor concert, and Pocono had one.

200,000 Jam Rock Festival at Pocono Track-Grace Lichstenstein (NYT July 9 '72)

LONG POND, Pa., July 8— An estimated 200,000 young people jammed the Pocono International Raceway today for a rain‐soaked, one‐day rock music festival the biggest youth gathering in the East since Woodstock three years ago.From as far away as California and Florida, the youngsters had come to hear the sounds of such groups as Three Dog Night; Faces; Emerson, Lake and Palmer; Humble Pie; Badfinger, and Edgar Winter. The promoters promised 10 hours of music for the $11 admission.

The scene as the music began at 1 P.M. was hot and crowded but generally calm. From an airborne helicopter, the mass of blue‐denimed bodies could be seen stretching across three‐quarters of the 600‐acre grassy infield, which is enclosed by the triangular auto racing track.First Act Cheered

The crowd cheered enthusiastically for the first act, Mother Night, but the reaction to Groundhogs and Claire Hamill was more restrained.A downpour began in mid afternoon and turned vast stretches of the ground into a sea of mud. Thousands of youngsters, blankets wrapped around their shoulders, trudged to shelter beneath the grand stands and in their cars while concert officials wrapped the stage equipment in yards of plastic.

“Anybody got a ride to New York?” one boy shouted plaintively as he peeked from beneath a sagging tent hastily erected under the grandstand in the mud.

When the concert resumed shortly after 6 P.M. it appeared that perhaps a third of the crowd had left. But the rest re turned, shivering, to the in field, standing shoulder to shoulder behind a 12‐foot wire fence that separated them from the huge stage.

Many of the youngsters had already been in the hills of Eastern Pennsylvania for 24 hours. They began arriving Friday afternoon, as thousands of cars and numerous back packing hitchhikers caused massive traffic jams on Interstate Route 80 south of the resort town of Mount Pocono near the track.

Friday night, a spokesman for Concert 10, Inc., the festival promoters, estimated that 30,000 people were camped in the area. The flickering light of campfires dotted the night, totally darkened by a power blackout in the area.

In the early morning hours today [July 9], Pennsylvania state troopers set up roadblocks on Routes 115 and 715 just out side the track, forcing festival goers to abandon their cars eight miles away and walk to the raceway.

From then on, a steady stream of newcomers filed through 10 gates along the high wire fence that encloses the grounds. The site of the throng was impossible to estimate accurately. Organizers said they had sold 125,000 tickets, but the Pennsylvania State Police put the crowd figure at nearly 200,000.

The raceway parking fields contained 40,000 cars, and all roads leading to the festival site were lined with parked cars stretching away for miles.The audience was a blend of high school youngsters new to the rock festival scene; older festivalgoers who spoke knowingly of Atlanta, Randalls Island, Strawberry Fields in Canada and Woodstock; a few tattooed motorcyclists, and an unknown number of drug dealers who quietly but openly peddled their wares as they circulated through the grounds. There were few blacks in the crowd.

At the gathering itself, there were no reports of deaths or major fights. Three hundred unarmed security men provided by the raceway patroled the crowd, but most youngsters were unaware of them as they sunned themselves barechested, drank wine and beer, embraced on blankets, smoked marijuana or simply listened to the music.

As night wore on, and the temperature dropped into the 50's, bonfires were started throughout the infield and groups of young people huddled around them to keep warm.

Rocco Urella, State Police Commissioner of Pennsylvania, said after touring the area in a helicopter that the festival seemed under control. However, he said, he was deploying 100 state police outside the raceway grounds to control traffic.

“Within a 15‐mile area around here it looks like the world's biggest garbage dump,” he said, adding that the police were beginning to tow cars off the roads to make room.

A festival spokesman said the concert would run until 6:30 A.M. because the medical officials felt it would not be wise to end the show when the thousands in the audience would have to make their way to their cars in the dark.

It is worth reading the entire Times article for a fuller picture of the concert, with the usual early 70s fixation on how many drug overdoses there might have been, and some other casual observations. Near the end of the article, there were some meaningful points about why so many young people had attended the Pocono concert:

Through hour‐long sets by Cactus, and Edgar Winter, the thousands of listeners remained standing in what spots was ankle‐deep mud, cheering wildly.

Although the promoters attributed the success of the event to the “name” acts, many had obviously had come just to be a part of the scene.

“It's something to do, man,” said 18‐year‐old Michael Turi of Edison, N.J., who was sitting near the stage with five of his friends. In their makeshift lean‐to was a pile of food. Describing the group's eight‐hour ride, he added:

“It was bumper to bumper. Only once in a while we'd stop and get out, and people from other cars would be going around giving out wine.”

A Comment Thread has some incredible stories from concertgoers (they can't really be pasted).

|

| The July 6 '74 Pottsville Republican discusses plans for another festival at Pocono Raceway |

Festival Revisited-1974

The Pocono International Raceway Festival in 1972 was everything the local community had feared back in 1970. Massive crowds beyond what the roads could absorb, bonfires, drugs, nudity--everybody was probably relieved that things hadn't gone worse. Still, just three weeks later, the second Schaefer 500 Indy Car race was held on July 29, 1972 (won this time by Joe Leonard), so the facility had been cleaned up and racing proceeded as normal. There may have been a Johnny Cash concert that weekend as well, but I can't pin that down. By 1974, Pocono had added a NASCAR feature to their Summer. Richard Petty won the Purolator 500 on August 4, 1974. Nonetheless, the raceway was privately owned, without deep corporate pockets, so they had to at least consider alternative sources of revenue.

The big comparison to the '72 Pocono concert was the huge "Summer Jam" rock concert at Watkins Glen International Race Course, on July 28, 1973. Featuring the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers Band and The Band, the show drew 600,000 fans to the Grand Prix track. In his Deadcast feature on the planning for the concert, Jesse Jarnow explained that the Summer Jam promoters (Jim Koplik and Shelly Finkel) had first asked about Pocono in the Fall of '72. They were turned down due to schedule conflicts, although the disastrous mess of the '72 show probably didn't leave the Pocono management eager. Still, the track probably needed the revenue, because there was another try in 1974.

"Campaign '74" at Long Pond (Pocono International Speedway) had been announced by its promoters, Electric Factory Concerts.So far, the announced acts for the noon to 9 p.m. festival on August 31 (Saturday) are the Allman Brothers, The Beach Boys, the Marshall Tucker Band, Duke Williams and the Extremes, and some unannounced acts.

There has been NO word from the promoters, but this column speculates that one of the unannounced bands just might be the tentatively reformed Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

They're going to charge $10 for the day--that price includes parking charges. No one will be allowed access to the track highway unless they have a ticket.

Hopefully, there will be no hassles. There was another rock festival at the race track, one that went off pretty successfully some time ago--the one with Humble Pie, Rod and the Faces and some other big names.

The Electric Factory was taking another stab at Pocono. The Allman Brothers Band, riding high on "Ramblin' Man" and "Jessica," were the most popular touring act in the country. Granted, Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones weren't touring, but the Allmans were the first band to book much of their Summer tour in football stadiums rather than just basketball arenas, and huge crowds were showing up.

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young would indeed tour in the late Summer. The quartet had attempted to record a follow up to their epic Deja Vu album, and had repeatedly come up short. They had booked a tour in anticipation of the album, however, and so even though there was no record CSNY went on tour anyway. There weren't a lot of dates, but they were all football stadiums or equally outsize venues. The Allmans' lesson wasn't lost on other bands.

The Beach Boys supported CSNY on a number of dates, so the speculation that the quartet was on the bill was probably a good one. The Electric Factory was thinking big. The Allman Brothers and CSNY were the two biggest tours in the country that Summer, and they were going to share the bill. Ticket demand would have dwarfed a football stadium--either headliner could pack a stadium--so a racetrack that could absorb 200,000 or more made sense.

Yet no more was heard of the 1974 Pocono concert. While the columnist (above) considered the 1972 festival to have been "pretty successful," my suspicion is that the local community and the cops didn't feel that way. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young ended up playing Cleveland Municipal Stadium on August 31. Cleveland Municipal had a football capacity of 75,000, and was one of the largest available stadiums, but it could still only absorb half the crowd that could have fit into Pocono.

While there are some articles from July of '74 promoting the Allman Brothers at Pocono, often with different opening acts (Edgar Winter, for example), I can find no trace of the actual concert. It seems that the Allman Brothers' Summer '74 tour ended August 24 in Mobile, AL, at Ladd Memorial Stadium, at the "Gulf Coast Summer Jam." The '74 Pocono concert must have been a bridge too far for Long Pond. Whether or not CSNY was actually ever contemplated, the Allman Brothers could have brought out a huge crowd on their own, but it was not destined to happen.

AftermathWith both Indy Car and NASCAR 500 mile races on the annual calendar, Pocono International Raceway had the anchor events to succeed as an auto racing facility. The track has had various ups and down over the decades, usually corresponding to the economics of auto racing at the time, but in general the Raceway has thrived. Currently Pocono has a NASCAR race, though not an Indy Car race, and it is regularly used for different types of local and regional racing. As noted, a Johnny Cash concert was scheduled for Pocono in late 1972, but I don't know if it was actually held. Otherwise, I am not aware of any music events of any significance have ever been held at Pocono International Raceway.

Like many auto racing facilities, Pocono International Raceway could have made an excellent concert facility, without interfering with the principal business of racing. Yet the initial event was so well-attended that the local community never seems to have considered a sequel. By the time the audience for auto racing and rock concerts had merged, some decades later, entirely new structures had built up to service the rock crowd, and the opportunity was gone.

|

| The back cover of the cd of Emerson Lake & Palmer's performance at Pocono Raceway on July 8, 1972 (released 2017) |

Appendix: July 8-9, 1972 Pocono Raceway Performers in Order of Appearance

All of the bands booked for the Pocono Festival were on tour for the Summer. Reviewing the status of each band gives us a good snapshot of the many bands touring the States in the Summer of '72. A look at the different arcs of each performer's career also gives us a picture of the bands for whom the Festival may have been their high water mark, versus those who would climb a lot farther (for some other interesting takes on the concert, see here).

Mother Night was a hard rock band from New York. They released their sole album on Columbia in 1972. According to the Times (above), they got a big cheer when they started, no doubt because the restless crowd was excited to hear some live music. If 100,000-plus cheering teenagers didn't give Mother Night a buzz, nothing would. Mother Night came onstage at 1:00pm. The next few performers followed sequentially.

Claire Hamill was an English singer/songwriter on Island Records. She had released her debut album One House Left Standing, back in 1971. Hamill was seen as a sort of English Joni Mitchell, a daunting reputation, but a sign of how highly regarded she had been. On her album, she was joined by heavy players like Terry Reid and David Lindley (who was working with Reid at the time). Still--a muddy field, 100,000 kids, one woman with an acoustic guitar. Who thought this was a good idea? Hamill was talented, but there's literally no way she could have made an impression. According to a Message Board Comment Thread, she was booed off the stage.

The Groundhogs were a psychedelic blues power trio who were pretty successful in England. United Artists had just released Hogwash, the Groundhogs fifth album. The band was on what would be their only American tour. The trio had originally formed to back visiting American blues artists who were touring England, so they were very excited to be touring the States. The Groundhogs had what is now considered their classic lineup, with guitarist and singer T.S. McPhee, supported by bassist Pete Cruickshank and drummer Ken Pustelnik. Shortly after this show, T.S. McPhee fell off a horse and broke his wrist, thus ending the US Tour. The Groundhogs stayed in England from then on, but they continued to perform well into the 21st century with various lineups.

It's worth comparing The Groundhogs to Claire Hamill from a booking perspective. The Groundhogs were a pretty shrewd booking. TS McPhee was an excellent guitarist, and the rhythm section drove hard. The Groundhogs' music was pretty basic. It had more subtlety than you might initially give it credit for, but coming on as opening act in a big venue was a good idea. The Groundhogs had a reasonable chance of making some new converts' who might check out the album when they got home. Claire Hamill, meanwhile, for all her talent and appeal, would have been simply lost. If the sound wasn't perfect--a pretty likely assumption--everything intriguing about her music would have been swallowed up. The Groundhogs, conversely, like most hard rockers, could still get something fun out of sound that was being blown around by the wind.

After the Groundhogs, the rain started to come down very heavily, and the music acts were put on hold.

|

| Ramatam's debut album, featuring guitarist April Lawton and drummer Mitch Mitchell, was released by Atlantic Records in 1972 |

Ramatam performed at 6:00pm, when the music started again. Ramatam had released their debut album in mid-72, and was being promoted by Atlantic Records as a kind of super-group. Along with ex-Hendrix drummer Mitch Mitchell, guitarist Mike Pinera (ex-Blue Image and ex-Iron Butterfly) and keyboard man Tommy Sullivan (Brooklyn Bridge), Atco made a big deal out of lead guitarist April Lawton. April was going to the "next big guitar hero," and while April was long-haired and skinny like most other guitar heroes, she was a girl. So this was going to be a very big deal, the first female guitar hero.

Ramatam's debut album was poorly produced and didn't have much in the way of material. But April Lawton could definitely play, and based on long ago Yahoo message boards, Lawton could really bring it on stage. So Ramatam might have been pretty good on a big festival stage, and after a few hours waiting out the rain, they must have been well-received (for more about the unique history of April Lawton's career, see here).

Bull Angus had released Free For All, their second album, on Mercury Records in 1972. The band was from Upstate New York somewhere, so they were a regional band.

|

| Cactus' final album on Atco, 'Ot 'N' Sweaty, released in 1972. Some of it had been recorded live at the Mar Y Sol Festival in Puerto Rico earlier in the year. |

Cactus was another hard rocking band, anchored by the driving rhythm section of bassist Tim Bogert and drummer Carmine Appice. The pair had been in Vanilla Fudge, and their bottom-heavy sound influenced a lot of bands, most notably Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin. In late 1969, Bogert and Appice were supposed to form a group with Jeff Beck, but Beck got in a serious auto accident and was out of action for a year. The pair ended up forming Cactus instead. Cactus were loud and hard, but more guitar and boogie oriented than the more R&B-influenced Vanilla Fudge.

At the time of the Pocono festival, Cactus's current album was Restrictions, their third album on Atco Records. By festival time, however, lead singer Rusty Day and guitarist Jim McCarty had quit the group. They had been replaced by lead singer Peter French, lead guitarist Werner Fritschings and keyboardist Duane Hitchings. The quintet would release one more Cactus album, 'Ot 'N' Sweaty, in August 1972. Part-live and part-studio, it gives a pretty good idea of how Cactus would have sounded at Pocono. Shortly after Pocono, Cactus broke up so that Bogert and Appice could finally work with Jeff Beck.

A band called Lace Pavement apparently played at 9:00pm. I can find nothing about them. I assume they were a local act, added at the last moment.

Edgar Winter had released a 1970 solo album (Entrance) and two albums leading Edgar Winter's White Trash (including the live Roadwork in March 1972). Edgar Winter, besides being known as Johnny's (equally albino) brother, was identified more as a saxophone and keyboard player rather than as just a vocalist. In White Trash, for example, Edgar wasn't the primary lead singer (Bobby LaCroix sang many of the songs). By mid-72, however, Edgar had left White Trash to their own devices, and formed the new Edgar Winter Group. His new, smaller band had Ronnie Montrose on lead guitar (ex-Boz Scaggs and ex-Van Morrison), Dan Hartmann on bass and vocals and drummer Chuck Ruff.

The Edgar Winter Group's debut album would not be released until November 1972. They Only Come Out At Night, produced by Rick Derringer (who would later replace Montrose as guitarist in the band) was a big success, driven by the hit guitar instrumental "Frankenstein." Even prior to the album, however, Edgar Winter was a big enough name that the group could tour steadily. A festival was a great place for the band to get heard by a huge number of people, given that they were a new configuration without an album.

There was another extensive delay for rain, presumably around 11pm. As noted above, it was decided not to cancel the concert, so that tens of thousands of people would not be hiking miles in rainy darkness trying to find their cars. The remaining acts, including the three headline acts, did not come on until 4am on Sunday, July 9.

|

| The back cover of the cd of Emerson Lake & Palmer's performance at Pocono Raceway on July 8, 1972 (released 2017) |

Emerson, Lake & Palmer were absolutely huge in the early 1970s, and all but single-handedly established "progressive rock" as a commercially viable proposition. ELP had formed out of the ashes of Emerson's 60s trio, The Nice. The Nice were progressive rock pioneers, featuring Emerson's formidable organ and piano skills, augmented by odd time signatures and orchestral accompaniment. Along with the difficult stuff, The Nice would do highly musical covers of Bob Dylan songs and the like. They were very popular in England. The Nice had ground to a halt by the end of 1969, and Emerson and Greg Lake teamed up, finding Palmer in early 1970. Almost from their inception, the band's merger of classically-themed pieces and loud rock virtuosity made them a huge concert attraction. ELP showed that rowdy young men could get just as excited about a 20-minute rock adaptation of a classical theme as they would for a blues boogie.

ELP had scored a modest hit single with Greg Lake's "Lucky Man" in 1970, but they were largely an album band. In June, 1972 ELP had released Trilogy, their third album on Island Records. It would reach #5 in the Billboard album charts.

ELP started off the last section of the concert at 4am. Their entire performance at Pocono was recorded and released on a CD box set in 2017.

The Faces and Rod Stewart were huge, and getting even bigger. Rod Stewart had joined the Faces in late 1969 the same year he began his solo career. He recorded both with the Faces and on his own, but he toured with the Faces. The Faces had added in a few Stewart hits to their concert repertoire. Another peculiarity was that Stewart's solo albums were on Mercury, while The Faces recorded for Warner Brothers. For all the complications (and there were plenty) it meant that two separate record companies put their promotional muscle behind every Faces tour.

Rod Stewart's third solo album, Every Picture Tells A Story, had been released by Mercury in July, 1971. The classic "Maggie May" became a huge single, reaching #1 on the Billboard charts for several weeks, and the album was equally successful. The record made Stewart a far bigger star than the Faces. Still, the Faces had released their excellent fourth album, A Nod Is As Good As A Wink (To A Blind Horse) in November 1971. It would reach #6 on the album charts, and the hit single "Stay With Me" also reached #6. In July of '72, Stewart would release his 4th album Never A Dull Moment, with another monster hit in "You Wear It Well." It's possible that FM stations were playing advance tracks of the album prior to the Pocono concert.

The original Faces lineup--with Stewart, guitarist Ronnie Wood, organist Ian McLagan, bassist Ronnie Lane and drummer Kenny Jones--were fantastic in concert. However many fans may have stayed through two rainstorms to see the Faces at 5:00am, they would have at least gotten a great set.

|

| Smokin', Humble Pie's 1972 release on A&M Records, was the first album with lead guitarist Clem Clempson in place of Peter Frampton. The popular song on FM radio was "30 Days In The Hole." |

Humble Pie had made a slow but steady rise through the States by touring incessantly since 1969. In late 71, their double album Rockin' The Fillmore finally broke them open fairly wide on FM radio stations across the country. Guitarist Peter Frampton had quit the band soon after, however. Humble Pie replaced Frampton with guitarist David "Clem" Clempson, and had produced their strongest studio album, Smokin'. Smokin' included the FM classic "30 Days In The Hole." Humble Pie frontman Steve Marriott had an incredible voice, and was as dynamic performer as there was in the rock universe. Bassist Greg Ridley was also a solid singer, and he and drummer Jerry Shirley laid down a thundering bottom. Clempson wasn't as good a singer as Frampton, but he was a great lead guitarist. Even at 6:00am, Humble Pie probably absolutely killed it.

As a rock'n'roll footnote, Humble Pie frontman Steve Marriott had been a huge pop star in England from 1965-68 with the Small Faces (their only American hit had been "Itchykoo Park"). The rest of the Small Faces were Ian McLagan, Ronnie Lane and Kenny Jones, now in the Faces with Rod and Ron. The Small Faces had never made it big in the States, but now its component parts were dominating a rock festival with hundreds of thousands of fans.

The J. Geils Band did the next-to-last set, probably somewhat shortened around 7:00am. Although the J. Geils Band would sell huge numbers of records in the 1980s, and were legendary live performers, they weren't well-known at this time, at least compared to the Faces, Humble Pie or Three Dog Night. The band was a legend in Boston and New England, but their reputation didn't extend much beyond that. They had released their second album on Atlantic, The Morning After, in October 1971. The Geils Band would initially become big by touring relentlessly--they had an exciting, dynamic live show--and playing at 7am at a racetrack in the mountains, however tired they may have been, was how they built an audience and became successful.

Three Dog Night closed the show, apparently starting off at 7:40am. Three Dog Night probably had it in their contract that they had to close the show. They may have regretted it when they had to stay another day and finally perform after dawn (guitarist Michael Allsup has some funny memories of the event). In terms of record sales, the band was huge. Their current album was Seven Separate Fools, their seventh album on Dunhill Records, all of which had reached the top 20. They had also had no less than eight Top 10 singles, including two that reached #1 ("Mama Told Me Not To Come" and "Joy To The World"). Their next single, "Black And White" would be released in August, and it too would go to #1.

|

| Cars parking wherever they could outside the Pocono Raceway, July 8 '72 |

For all their huge popularity, and polished stage show, Three Dog Night did not have the cachet of other groups. Three Dog Night covered songs by other songwriters, and had excellent, catchy arrangements, well-sung (they had three lead singers) and well-played. But since their music wasn't "original" they had a sort of Authenticity Gap, something that mattered a lot in the '70s. Because they played all covers, they weren't seen as "expressing themselves," or something like that. Whether you think that's fair or not, Three Dog Night had sold more records than any act at the concert--possibly more than all of them put together--and by any mark were a huge band. But when you read message boards fondly recalling the mud and mayhem, everyone seems to remember Humble Pie and The Faces, and somehow Three Dog Night just passed everyone by.

Badfinger and Black Sabbath were both on the bill, but canceled and did not perform.

No comments:

Post a Comment